KnowledgeStar is a corporation that consults with large and small organizations to transform themselves into learning cultures. Contact us at David(at)KnowledgeStar.(com)

Posted in Advancement, Continuous Learning, corporate training, Education, Formal Learning, Learning, Training & Development | Tagged Amy C. Edmondson, failure,Harvard, intelligent failure, Learning, Learning Culture, Organizational psychology, Prof. Edmondson, training, training & Development | Leave a Comment »

This post written by Susan Fry and David Grebow

“Push” learning has gone the way of the cassette tape, tube television and electric typewriter.

Leading educators and trainers now regard push learning as inefficient, suboptimal and outdated. Even many schools, often the slowest institutions to change, are rapidly making the transition away from that model.

Yet, despite the fact that “push learning” is clearly not suited for today’s “economy of ideas,” corporations have been surprisingly reluctant to make the necessary change.

Why?

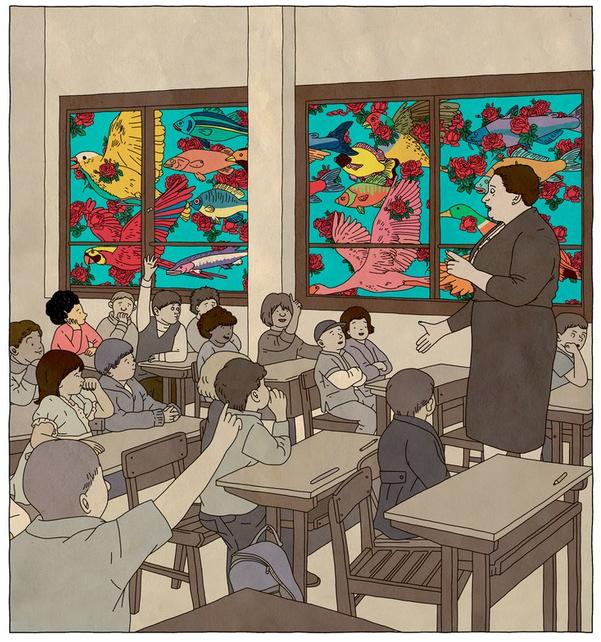

The reason may well lie in the fact that a “pull” learning culture is truly democratic. It’s a culture that encourages and supports everyone to explore and demonstrate their initiative and abilities, allowing the best to rise to the top based on merit.

That sounds like a great benefit to any organization. But when put into practice, the concept can prove to be quite revolutionary.

Throughout history, providing access to knowledge has been a way to control who gained power, wealth and status.

Learning and training are often hoarded and carefully doled out to people upon whom top management wish to confer success. Often, they are golden keys to elite private club that are given to friends’ children, colleagues, and clients, alumni from the same university, people of the same culture, class or color.

There can be no doubt that in the last 50 years, countries with the world’s leading economies have worked to erode discrimination and provide greater employment opportunities to people regardless of their race or gender.

It’s time organizations make another much-needed cultural shift, and “tear down the wall” by replacing the old, “push” learning culture with a “pull” culture that ensures equal opportunity learning.

KnowledgeStar is a corporation that consults with large and small organizations to transform themselves into learning cultures. Contact us at David(at)KnowledgeStar.(com)

Posted in Advancement, Continuous Learning, corporate training, Education, Formal Learning, Learning, Training & Development | Tagged Amy C. Edmondson, failure,Harvard, intelligent failure, Learning, Learning Culture, Organizational psychology, Prof. Edmondson, training, training & Development | Leave a Comment »

This post written by Susan Fry and David Grebow

“Push” learning has gone the way of the cassette tape, tube television and electric typewriter.

Leading educators and trainers now regard push learning as inefficient, suboptimal and outdated. Even many schools, often the slowest institutions to change, are rapidly making the transition away from that model.

Yet, despite the fact that “push learning” is clearly not suited for today’s “economy of ideas,” corporations have been surprisingly reluctant to make the necessary change.

Why?

The reason may well lie in the fact that a “pull” learning culture is truly democratic. It’s a culture that encourages and supports everyone to explore and demonstrate their initiative and abilities, allowing the best to rise to the top based on merit.

That sounds like a great benefit to any organization. But when put into practice, the concept can prove to be quite revolutionary.

Throughout history, providing access to knowledge has been a way to control who gained power, wealth and status.

Learning and training are often hoarded and carefully doled out to people upon whom top management wish to confer success. Often, they are golden keys to elite private club that are given to friends’ children, colleagues, and clients, alumni from the same university, people of the same culture, class or color.

There can be no doubt that in the last 50 years, countries with the world’s leading economies have worked to erode discrimination and provide greater employment opportunities to people regardless of their race or gender.

It’s time organizations make another much-needed cultural shift, and “tear down the wall” by replacing the old, “push” learning culture with a “pull” culture that ensures equal opportunity learning.

KnowledgeStar is a corporation that consults with large and small organizations to transform themselves into learning cultures. Contact us at David(at)KnowledgeStar.(com)